Decision Making Without Meetings

Last weekend, my girlfriend told me about a meeting at her company. The meeting was called to decide on which part to use when their original choice was unavailable. The meeting was an hour long and included 10 people. That's 10 person hours to make a single decision... about a single part.

You can probably envision this meeting.

Someone calls the meeting so that, if something goes wrong, they can cite the meeting in their defense. Ten people are invited because no one is empowered to make a decision or, if they are, the other 9 people will complain if they don't get to voice their opinion. Most of the time is spent on everyone taking turn saying their bit so that everyone's egos are stroked.

The agenda and options were unclear. If they were, the necessary people could easily make their suggestion (online and asyncronously), and the decision-maker could move forward with an alternative. Instead, 10 hours were wasted on a single part.

These are the times that try men's souls.

This bullshit happens everywhere, including at Google, where I worked.

If you have to be at work for 8+ hours anyway, why not kill an hour with a meeting? If you didn't call the meeting, you can probably turn your brain off for most of it until you get to speak. These meetings are egregious wastes of time.

When you start working remotely and you reclaim ownership of your time, you'll start to really resent them. Then you'll figure out alternative solutions.

Of course, there is a time and a place for meetings. At Tortuga, we emphasize regular one-on-ones and team meetings. Twice per year, we sub out a one-on-one for a Mid-Year or End of Year check in, known as a Performance Review at other companies. We try to avoid wasting time in meetings.

Good luck reaching consensus among 10 people. This is not an effective way to make a decision. Ten people are good for making suggestions, not decisions. Solicit as many opinions as you like. Count as many votes as you like. But empower someone to make the decision and to be responsible for the results.

Here's how we solicit input and make decisions remotely and asyncronously at Tortuga.

Input and Debate

Getting opinions is easy. Everyone has one.

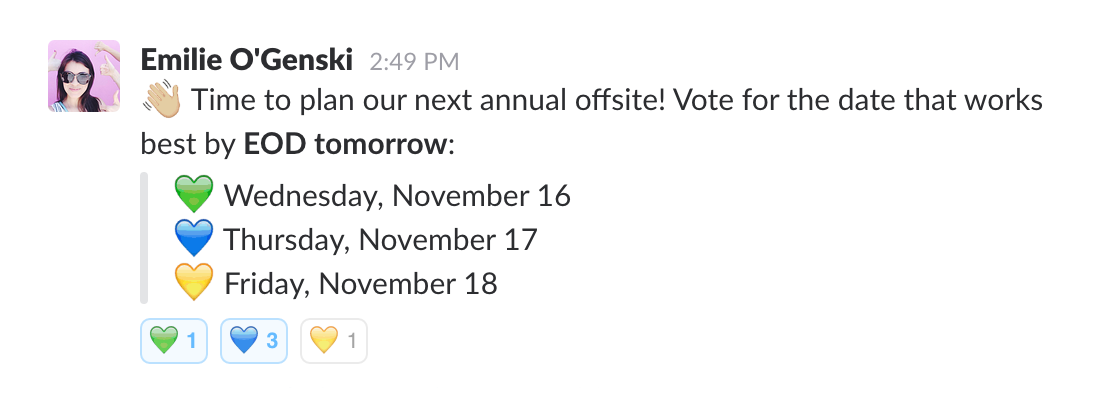

If you want as many as possible, you can email the team or build a simple Slack "poll" to collect votes. We will sometimes do this regarding a specific product feature or trade off. The poll taker must always clarify that the poll will be one data point that we will use in the decision making process. Our design process is not a direct democracy.

Collecting input from a smaller team is easy. At Tortuga's size, most of our "teams" are 2-3 people from across disciplines or with different responsibilities within a discipline.

For example, our Web Team is Garrett (visual design and development), Taylor (marketing), and me (CEO). Garrett takes the lead, but ideas can come from anywhere.

New projects often start with a Google Doc outlining goals. We leave comments on the doc to reach consensus on those goals. As the project moves forward into design and later dev phases, Garrett shares drafts via Invision and Taylor writes copy in Google Docs. Both tools allow all three of us to see the work, not just talk about ideas in theory. We can leave comments and have threaded discussions within the tools and do so asyncronously, on our own time, without calling a meeting. Providing feedback asynchronously lets us batch this work and to think about it before commenting. Gasp!

If we get stuck on any contentious points, we can jump on a call to talk it through. That call does not need to be an hour long and will only cover the decisions that we couldn't work out via commenting. These calls aren't often needed as we're usually able to come to a resolution in the comments. Yes, comment sections can be useful.

Disagree and Commit

After input has been given and questions have been resolved, the project lead (or Batman as Buffer says) can make a decision and move foward.

Here I should address, "What happens if you didn't get your way?"

No one is keeping score. You, the individual, do not win or lose when a decision is made. We either succeed as a team or we fail as a team.

No one, including me, gets their way all the time. That's okay. Voice your opinion when appropriate. It's okay to disagree, even forcefully. Then, when a decision is made, get behind it and work to make it successful.

Amazon calls this idea "disagree and commit." Here's what Jeff Bezos said about "high velocity decision making" in Amazon's 2016 Letter to Shareholders.

[U]se the phrase “disagree and commit.” This phrase will save a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes.

This isn’t one way. If you’re the boss, you should do this too. I disagree and commit all the time. We recently greenlit a particular Amazon Studios original. I told the team my view: debatable whether it would be interesting enough, complicated to produce, the business terms aren’t that good, and we have lots of other opportunities. They had a completely different opinion and wanted to go ahead. I wrote back right away with “I disagree and commit and hope it becomes the most watched thing we’ve ever made.” Consider how much slower this decision cycle would have been if the team had actually had to convince me rather than simply get my commitment.

Disagreeing or playing devil's advocate is helpful in adding rigor to the decision-making process. However, once a decision is made, everyone must be all in.

You can't undermine a decision that you disagreed with to prove a point or to make someone else "wrong." Making the decision fail doesn't prove that you were "right." It just means you're a shitty teammate.

Reaching a Stalemate

When we can't reach a consensus or when feelings are equally strong on both sides of a decision, we go to our back up plan.

If we can't reach consensus on a decision on the Product Team, then I become the Decider.

The Decider's opinion doesn't "win." The Decider's job is to be the arbitrator in these situations. For example, imagine that the votes on a decision are 2-to-1 with the Decider in the minority. In most of those cases, the majority vote should probably be the final decision. The Decider should have a damn good reason to overrule the vote count. "Because I'm the CEO" is not a good enough reason. If the Decider abuses this power, s/he will no longer be the Decider.

Ultimately, the Decider must make the decision and own it. Everyone else must then commit to making that decision a success.

Teams only work when everyone is pulling in the same direction.

Recap

Many of these ideas can be applied in colocated businesses too. Debate and decision making are broken at many companies.

How many of those 10-person, hour-long meetings have you sat through? How many decisions have you seen overridden by the highest paid person's opinion (HiPPO)?

We can do better.

- Present ideas and provide feedback using a collaborative, asynchronous tool (Invision, Google Docs).

- Resolve questions in the tool. When not possible, have a short call with a specific agenda limited to resolving those questions.

- Disagree and commit.

- When all else fails, empower The Decider.

Fred Perrotta Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.